Deborah Tannen

Deborah Tannen | |

|---|---|

Deborah Tannen in 2013 | |

| Born | June 7, 1945 |

| Education | |

| Occupations |

|

| Notable work | You Just Don't Understand |

| Website | deborahtannen |

Deborah Frances Tannen (born June 7, 1945) is an American author and professor of linguistics at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. Best known as the author of You Just Don't Understand, she has been a McGraw Distinguished Lecturer at Princeton University and was a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences following a term in residence at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.

Tannen is the author of thirteen books, including That's Not What I Meant! and You Just Don't Understand, the latter of which spent four years on the New York Times Best Sellers list, including eight consecutive months at number one.[1] She is also a frequent contributor to The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, and Time magazine, among other publications.[2]

Education

[edit]Tannen graduated from Hunter College High School and completed her undergraduate studies at Harpur College (now part of Binghamton University) with a B.A. in English literature. Tannen went on to earn a master's in English literature at Wayne State University. Later, she continued her academic studies at UC Berkeley, earning an M.A. and a Ph.D. in linguistics (1979) with a dissertation entitled "Processes and consequences of conversational style".[3] She took up a position at Georgetown in 1979 and subsequently became a Distinguished University Professor in Linguistics there.[4]

Writing career

[edit]Tannen has also written nine general-audience books on interpersonal communication and public discourse as well as a memoir. She became well known in the United States after her book You Just Don't Understand: Women and Men in Conversation was published in 1990. It remained on the New York Times Best Seller list for nearly four years, and was subsequently translated into 30 other languages.[1] She has written several other general-audience books and mainstream articles between 1983 and 2017.

Two of her other books, You Were Always Mom's Favorite!: Sisters in Conversation Throughout Their Lives and You're Wearing THAT?: Understanding Mothers and Daughters in Conversation were also New York Times best sellers. The Argument Culture received the Common Ground Book Award, and I Only Say This Because I Love You received a Books for a Better Life Award.

Research

[edit]Overview

[edit]Tannen's main research has focused on the expression of interpersonal relationships in conversational interaction. Tannen has explored conversational interaction and style differences at a number of different levels and as related to different situations, including differences in conversational style as connected to the gender[5] and cultural background,[6] as well as speech that is tailored for specific listeners based on the speaker's social role.[7] In particular, Tannen has done extensive gender-linked research and writing that focused on miscommunications between men and women, which later developed into what is now known as the genderlect theory of communication. However, some linguists have argued against Tannen's claims from a feminist standpoint.[8]

Tannen's research began when she analyzed her friends while working on her Ph.D. Since then, she has collected several naturally occurring conversations on tape[9] and conducted interviews as forms of data for later analysis. She has also compiled and analyzed information from other researchers in order to draw out notable trends in various types of conversations, sometimes borrowing and expanding on their terminology to emphasize new points of interest.

Gender differences in US family interaction

[edit]Tannen highlighted the "Telling Your Day" ritual that takes place in many U.S. families, in which, typically, the mother in a two-parent family encourages a child to share details (about their day which the mother has typically already heard about) with the father.[5] She also emphasizes the common occurrence of the "troubles talk" ritual in women.[5] This ritual involves a woman sharing details about "a frustrating experience" or other previously encountered problem with a confidant. She cites this ritual as an example of how, for many women, closeness is established through sharing personal details.[5] As one example of gender-linked misinterpretations, Tannen points out that a man who is on the receiving end of "troubles talk" from his wife will often take the mention of a problem and how it was handled as an invitation to pass judgment, despite the fact that "troubles talk" is simply an expository experience meant to enhance emotional connections.

Interplay of connection maneuvers and power maneuvers in family conversations

[edit]Tannen once described family discourse as "a prime example…of the nexus of needs for both power and connection in human relationships.[5] She coined the term "connection maneuvers" to describe interactions that take place in the closeness dimension of the traditional model of power and connection; this term is meant to contrast with the "control maneuvers", which, according to psychologists Millar, Rogers, and Bavelas, take place in the power dimension of the same model.[5]

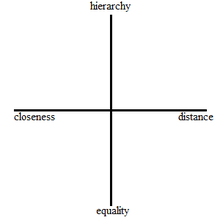

Tannen challenged the conventional view of power (hierarchy) and connection (solidarity) as "unidimensional and mutually exclusive" and offered her own kind of model for mapping the interplay of these two aspects of communication, which takes the form of a two-dimensional grid (Figure 1).

In this model, the vertical axis represents the level of power in the interaction, and the horizontal axis represents connection. Having presented this model, Tannen proposed that in the American paradigm, a sibling relationship would be mapped in the bottom left quadrant, as there is a high level of closeness and a relative equality that is not comparable to the power dynamic in an American parent/child relationship.[5] Using this new model, Tannen argues that connection maneuvers do not only occur independently of control maneuvers. Among other examples, she mentions a wife who refuses to let her husband take over making popcorn by saying "You always burn it".[5] According to Tannen, the wife's resistance to her husband's request is a control maneuver, but by citing a potential undesirable effect for her family (i.e. burnt popcorn), she ties a connection maneuver into her attempt to enforce a decision.

Tannen also highlights ventriloquizing – which she explains as a "phenomenon by which a person speaks not only for another but also as another"[10] – as a strategy for integrating connection maneuvers into other types of interactions. As an example of this, she cites an exchange recorded by her research team in which a mother attempts to convince her son to pick up his toys by ventriloquizing the family's dogs: "[extra high pitch] We're naughty, but we're not as naughty as Jared".[10]

Conversational style

[edit]Tannen describes the notion of conversational style as "a semantic process" and "the way meaning is encoded in and derived from speech".[9] She cites the work of R. Lakoff and J. Gumperz as the inspiration behind her thinking. According to Tannen, some features of conversational style are topic (which includes type of topics and how transitions occur), genre (storytelling style), pace (which includes rate of speech, occurrence or lack of pauses, and overlap), and expressive paralinguistics (pitch/amplitude shifts and other changes in voice quality).[9]

"High-involvement" vs. "high-considerateness"

[edit]Based on a two-and-a-half hour recording of Thanksgiving dinner conversations with friends, Tannen analyzed the two prevailing conversational styles among the six participants, which she divided evenly between the categories of New Yorker and non-New Yorker.[9] Upon analyzing the recording, Tannen came to the conclusion that the speech of the New Yorkers was characterized by exaggerated intonations (paralinguistics), overlapping speech between two or more speakers, short silences, and machine-gun questions, which she defines as questions that are "uttered quickly, timed to overlap or latch onto another's talk, and characterized by reduced syntactic form".[9] The style of the non-New Yorkers was opposite that of the New Yorkers in all regards mentioned above; furthermore, the non-New Yorkers were caught off-guard by the New Yorkers' exaggerated intonation and interrupting questions, two factors that discouraged them from finishing their conversations at some points.[9] Tannen refers to the New Yorkers' style as "high-involvement" and the unimposing style of the non-New Yorkers as "high-considerateness".[9]

Indirectness in work situations

[edit]Tannen has expressed her stance against taking indirect speech as a sign of weakness or as a lack of confidence; she also set out to debunk the idea that American women are generally more indirect than men.[7] She reached this conclusion by looking through transcripts of conversations and interviews, as well as through correspondence with her readers. One example she uses against the second idea comes from a letter from a reader, who mentioned how his Navy superior trained his unit to respond to the indirect request "It's hot in this room" as a direct request to open the window.[7] A different letter mentions the tendency of men to be more indirect when it comes to expressing feelings than women.[7]

Tannen also mentions exchanges where both participants are male, but the two participants are not of equal social status. As a specific example, she mentions a "black box" recording between a plane captain and a co-pilot in which the captain's failure to understand the co-pilot's indirect conversational style (which was likely a result of his relatively inferior rank) caused a crash.[7]

Indirectness as a sociocultural norm

[edit]During a trip to Greece, Tannen observed that comments she had made to her hosts about foods she had not seen yet in Greece (specifically, scrambled eggs and grapes) had been interpreted as indirect requests for the foods.[11] This was surprising to her, since she had just made the comments in the spirit of small talk. Tannen observed this same tendency of Greeks and Greek-Americans to interpret statements indirectly in a study[6] that involved interpreting the following conversation between a husband and a wife:

- Wife:

John's having a party. Wanna go?

Husband:Okay.

[later]

Wife:Are you sure you want to go to the party?

Husband:Okay, let's not go. I'm tired anyway.

The participants – some Greeks, some Greek-Americans, and some non-Greek Americans – had to choose between the following two paraphrases of the second line in the exchange:

- [1-I]:

My wife wants to go to this party, since she asked. I'll go to make her happy.

[1-D]:My wife is asking if I want to go to a party. I feel like going, so I'll say yes.

Tannen's findings showed that 48% of Greeks chose the first (more indirect) paraphrase, while only 32% of non-Greek Americans chose the same one, with the Greek-Americans scoring closer to the Greeks than the other Americans at 43%. These percentages, combined with other elements of the study, suggest that the degree of indirectness a listener generally expects may be affected through sociocultural norms.

Tannen provides an overview to how culture and power may subconsciously influence a speaker's preference for indirectness in her 1994 New York Times Magazine article "How to Give Orders Like a Man."[12]

Agonism in written academic discourse

[edit]Tannen analyzed the agonistic framing of academic texts, which are characterized by their "ritualized adversativeness".[13] She argued that expectations for academic papers in the US place the highest importance on presenting the weaknesses of an existing, opposing, argument as a basis for bolstering the author's replacement argument.[13] According to her, agonism limits the depth of arguments and learning, since authors who follow the convention pass up opportunities to acknowledge strengths in the texts they are arguing against; in addition, this places the newest, attention-grabbing works in prime positions to be torn apart.[13]

Publications

[edit]- Lilika Nakos (Twayne World Authors Series, G. K. Hall, 1983)

- Conversational Style: Analyzing Talk Among Friends (1984; 2nd Edition Oxford University Press, 2005)

- That's Not What I Meant! How Conversational Style Makes or Breaks Relationships (Ballantine, 1986, ISBN 0-345-34090-6)

- Talking Voices: Repetition, dialogue, and imagery in conversational discourse (Cambridge University Press, 1989, hardcover ISBN 0-521-37001-9, paperback ISBN 0521379008, 2nd edition 2007)

- You Just Don't Understand: Women and Men in Conversation (Ballantine, 1990, ISBN 0-688-07822-2; Quill, 2001, ISBN 0-06-095962-2)

- Talking from 9 to 5: Women and Men at Work (Avon, 1994, ISBN 0-688-11243-9; ISBN 0-380-71783-2)

- Gender and Discourse (Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-19-508975-8; ISBN 0-19-510124-3)

- The Argument Culture: Stopping America's War of Words (Ballantine, 1998, ISBN 0-345-40751-2)

- I Only Say This Because I Love You: Talking to Your Parents, Partner, Sibs, and Kids When You're All Adults (Ballantine, 2001, ISBN 0-345-40752-0)

- You're Wearing THAT?: Mothers and Daughters in Conversation (Ballantine, 2006, ISBN 1-4000-6258-6)

- You Were Always Mom's Favorite!: Sisters in Conversation Throughout Their Lives (Random House, 2009, ISBN 1-4000-6632-8)

- Finding My Father: His Century-Long Journey from World War I Warsaw and My Quest to Follow (Ballantine Books, 2020, ISBN 9781101885833)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "You Just Don't Understand". Archived from the original on July 9, 2010.

- ^ "General Audience Articles". Deborah Tannen. Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- ^ "Publications | Linguistics". lx.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ^ "Georgetown University Faculty Directory". gufaculty360.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Deborah Tannen (2003). "Gender and Family Interaction". In J. Holmes; M. Meyerhoff (eds.). The Handbook on Language and Gender. Oxford, UK & Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell. pp. 179–201.

- ^ a b Deborah Tannen (1981). "Indirectness in Discourse: Ethnicity as Conversational Style". Discourse Processes. 1981. 4 (3): 221–238. doi:10.1080/01638538109544517.

- ^ a b c d e Deborah Tannen (2000). "Indirectness at Work". In J. Peyton; P. Griffin; W. Wolfram; R. Fasold (eds.). Language in Action: New Studies of Language in Society. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. pp. 189–249.

- ^ "Deborah Tannen". Key Thinkers in Linguistics and the Philosophy of Language. Edinburg: Edinburgh University Press. 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f g Deborah Tannen (1987). "Conversational Style". Psycholinguistic Models of Production. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. pp. 251–267.

- ^ a b Deborah Tannen (2001). "Power maneuvers or connection maneuvers? Ventriloquizing in family interaction". In D. Tannen; J. E. Alatis (eds.). Linguistics, Language, and the Real World: Discourse and Beyond: Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. pp. 50–61.

- ^ Tannen, Deborah (1975). "Communication mix and mixup, or how linguistics can ruin a marriage". San Jose State Occasional Paper in Linguistics: 205–211.

- ^ Tannen, Deborah (28 August 1994). "How to Give Orders Like a Man". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Tannen, Deborah (2002). "Agonism in academic discourse". Journal of Pragmatics. 34 (10–11): 1651–1669. doi:10.1016/s0378-2166(02)00079-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Griffin, Em (2011). "Genderlect Styles of Deborah Tannen (ch. 34)". Communication: A First Look at Communication Theory (8th. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 435–446. ISBN 978-0-07-353430-5. Detailed chapter outline

- Speer, Susan (2005). "Gender and language: 'sex difference' perspectives". In Speer, Susan A. (ed.). Gender talk: feminism, discourse and conversation analysis. London New York: Routledge. pp. 20–45. ISBN 9780415246446.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Deborah Tannen's faculty page, Georgetown University.

- "Sisters Speak In 'You Were Always Mom's Favorite'". Susan Stamberg interview with Tannen. Morning Edition, National Public Radio, 8 September 2009. (Transcript and audio link.)

- Works by or about Deborah Tannen at the Internet Archive

- Communicating With Style-An Interview with Deborah Tannen.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1945 births

- Living people

- 21st-century American Jews

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American women writers

- American women linguists

- American women non-fiction writers

- Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences fellows

- Communication scholars

- Fellows of the Linguistic Society of America

- Georgetown University faculty

- Harpur College alumni

- Hunter College High School alumni

- Jewish American academics

- Jewish American non-fiction writers

- Jewish women writers

- Linguists from the United States

- Princeton University faculty

- Psycholinguists

- Sociolinguists

- University of California, Berkeley alumni

- Wayne State University alumni